Motion In a Plane Class 11 notes Physics Chapter 4

Introduction

In the previous chapter, we have learnt about "Motion in a Straight Line". In this chapter, we shall focus Motion In a Plane. In order to describe motion of an object in two dimensions (a plane) or three dimensions (space), we need to use vectors to describe the physical quantities. Therefore, it is first necessary to learn the language of vectors. What is a vector? How to add, subtract and multiply vectors ?

We shall learn this to enable us to use vectors for defining velocity and acceleration in a plane. We then discuss motion of an object in a plane. As a simple case of motion in a plane, we shall discuss motion with constant acceleration and treat in detail the projectile motion.

Scalars and Vectors

In physics, we can classify quantities as scalars or vectors. Basically, the difference is that a direction is associated with a vector but not with a scalar.

(i). Scalars

A scalar quantity is a quantity with magnitude only. It is specified completely by a single number, along with the proper unit. Scalars can be added, subtracted, multiplied and divided just as the ordinary numbers. Examples : current, speed, pressure etc.

(ii). Vectors

A vector quantity is a quantity that has both a magnitude and a direction and obeys the triangle law of addition or equivalently the parallelogram law of addition. Examples : displacement, velocity, acceleration, momentum etc.

(iii). Characteristics of Vectors

Following are the characteristics of vectors:

- These possess both magnitude and direction.

- These do not obey the ordinary laws of Algebra.

- These change if either magnitude or direction or both change.

- These are represented by bold-faced letters or letters having arrow over them.

Recommended Books

- NCERT Textbook For Class 11 Physics Part 1 & 2

- CBSE All In One Physics Class 11 2022-23 Edition

- Oswaal CBSE Chapterwise Question Bank Class 11 Physics Book

- Modern's abc Plus of Physics for Class-11 (Part I & II)

Read also: Laws of Motion Class 11 Physics Notes Chapter 5

How to Represent a Vector?

In books a vector is either represented by a bold face type of its symbol, or by an arrow placed on its symbol. For example, displacement S can be either represented by S or by `\vec{S}`.

Graphically, a vector is represented by a line segment, with an arrow at one of its ends. The length of the line segment is proportional to the magnitude of the vector and the arrow head tells the direction of the vector. The magnitude of a vector `\vec{S}` is often called its absolute value and is denoted as |`\vec{S}`|or simply S.

The Dot and Cross Product of Two Vectors

(i). The Dot Product of Two Vectors

The scalar product or dot product of any two vectors `\vec{A}` and `\vec{B}`, denoted as `\vec{A}` . `\vec{B}` (read as `\vec{A}` dot `\vec{B}`) is defined as

`\vec{A}` . `\vec{B}` = AB cosθ

Where A & B are magnitudes of vectors `\vec{A}` and `\vec{B}` respectively and θ is the smaller angle between them. Dot product is called scalar product as A, B and cosθ are scalars. Both vectors have a direction but their scalar product does not have a direction.

Read also: Chemical Bonding and Molecular Structure Class 11 Notes Chemistry Chapter 4

Properties

Dot product is commutative

A . B = B . ADot product is distributive

A . (B + C) = A . B + A . C

Dot product of a vector with itself gives square of its magnitude

A . A = AA cosθ = A

A . (λB) = λ(A . B)

where λ is a real number

- `\hat{i}` . `\hat{j}` = `\hat{j}` . `\hat{k}` = `\hat{k}` . `\hat{i}` = 0

- `\hat{i}` . `\hat{i}` = `\hat{j}` . `\hat{j}` = `\hat{k}` . `\hat{k}` = 1

(ii). The Cross Product of Two Vectors

The vector product or cross product of any two vectors `\vec{A}` and `\vec{B}`, denoted as `\vec{A}` x `\vec{B}` (read as `\vec{A}` cross `\vec{B}`) is defined as

`\vec{A}` x `\vec{B}` = AB sinθ

Where A & B are magnitudes of vectors `\vec{A}` and `\vec{B}` respectively and θ is the smaller angle between them. Cross product is called vector product as A, B and sinθ are scalars. Both vectors have a direction and their vector product has a same direction.

Read also: Conceptual Questions for Class 11 Physics Chapter 4 Motion in a Plane

Properties

The vector product is do not have Commutative Property.

A×B = – (B×A)

The following property holds true in case of vector multiplication

(kA)×B= k(A×B) =A×(kB)

If the given vectors are collinear then

A×B= 0

Following the above property, We can say that the vector multiplication of a vector with itself would be

A×A= |A||A|sin0 `\hat{n}` = 0

Also in terms of unit vector notation

`\hat{i}×\hat{i}=\hat{j}×\hat{j}=\hat{k}×\hat{k}=0`

From the above discussion it also follows that

`\hat{i}×\hat{j}=\hat{k}=−\hat{j}×\hat{i}`

`\hat{j}×\hat{k}=\hat{i}=−\hat{k}×\hat{j}`

`\hat{k}×\hat{i}=\hat{j}=−\hat{i}×\hat{k}`

Position and Displacement Vectors

(i). Position vector:- It is used to describe the position of an object in space. For this we have to choose a reference frame. Suppose the object is moving in a plane. We can represent that plane by x-y plane with its origin at O. Position vector of the object is the vector joining the origin to the point where the object lies directed from origin to the point. It is usually denoted by `\vec{r}`.

(ii). Displacement vector:- When an object is displaced from its position at point P to a new position at point P' (say), then the vector `\vec{PP'}` having its tail at P and head at P' is called the displacement vector of the object corresponding to its motion from P to P'.

Types of Vector

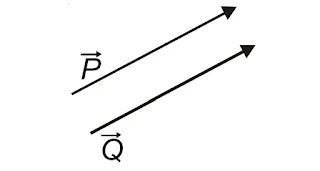

(i). Equal vectors

Two vectors having same direction and equal magnitude are said to be equal vectors. This is the necessary and sufficient condition for any two vectors to be equal.If two vectors P and Q are equal, we can write P=Q

(ii). Unit Vector

A vector having its magnitude equal to one is known as unit vector. In order to denote a unit vector we use cap (^) sign above the symbol of the vector. Unit vector has no unit.

`\hat{A}=\frac {\vec{A}}{\vec{|A|}}`

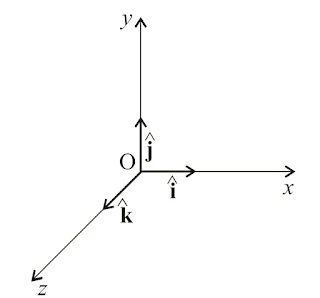

There are predefined unit vectors along x, y and z-axis which are `\hat{i}`, `\hat{j}` and `\hat{k}` respectively. Unit vectors are used to represent the direction.

(iii). Zero vector

A vector with zero magnitude and an arbitrary direction is called a zero vector. It is presented by `\vec{0}` and also known as Null vector.

(iv). Negative of a Vector

The vector whose magnitude is same as that of A but the direction is opposite to that of vector A is called a negative of A and is represented by -A.

(v). Parallel vectors

A and B are said to be parallel vectors if they have same direction,and may or may not have equal magnitude (A॥B). If the directions are opposite, then A is anti-parallel to B.

(vi). Coplanar Vectors

Vectors are said to be coplanar if they lie in the same plane or they are parallel to the same plane, otherwise they are said to be non-coplanar vectors.

Multiplication of Vectors by Real Numbers

When a vector `\vec{A}` is multiplied by a real number n, the quantity obtained is a vector n`\vec{A}` whose magnitude is n times that of the original vector. |n`\vec{A}`| = n|`\vec{A}`|. Its direction might be the same or opposite to that of the original vector depending upon whether n is positive or negative.

- If n is a positive number, n`\vec{A}` and `\vec{A}` have the same direction.

- If n is a negative number, n`\vec{A}` and `\vec{A}` have opposite directions.

- If n is zero, the magnitude of n`\vec{A}` is also zero. Such a vector, whose magnitude is zero is called a zero vector or a null vector and is denoted by `\vec{0}`. Since the magnitude of a null vector is zero, its direction cannot be specified.

- If n is a scalar quantity rather than just being a pure number, then the dimension of n`\vec{A}` is the product of dimensions of n and A.

Addition of Vectors

Vectors cannot be added by simple addition of numbers as this combined effect is direction dependent. You will have to use the following method.

(i). Triangular Law of Vector Addition

Let two vectors `\vec{A}` and `\vec{B}`, be represented in magnitude as well as direction by two sides of a triangle taken in same order, then the third side of the triangle taken in opposite order, represents the sum to two vectors.

In the figure, vectors `\vec{A}` and `\vec{B}` have an angle θ between them. Let the resultant be `\vec{R}` making an angle α with `\vec{A}`. SN is perpendicular dropped from S on the line OP. A, B, R are taken as magnitude of `\vec{A}`, `\vec{B}` and `\vec{R}`.

In triangle ONS,

`ON=A+B.cos\theta` and `SN=B.sin\theta`

`R^{2}=(A+B.cos\theta)^2+(B.sin\theta)^2`

`R^{2}=A^{2}+B^{2}cos^{2}\theta +2AB.cos\theta +B^{2}sin^{2}\theta`

`R^{2}=A^{2}B^{2}(cos^{2}\theta +sin^{2}\theta)+2AB.cos\theta`

`R^{2}=A^{2}+B^{2}+2AB.cos\theta`

`R=\sqrt{A^{2}+B^{2}+2AB.cos\theta}`

`tan\alpha=\frac{SN}{ON}=\frac{B.sin\theta}{A+B.cos\theta}`

(ii). Parallelogram Law of Vector Addition

If two vectors are represented in magnitude and direction by two adjacent sides of a parallelogram drawn from a point, then the diagonal of the parallelogram passing through that point will represent their resultant in magnitude and direction.

Vectors `\vec{A}` and `\vec{B}`are represented by two side OP and OQ of parallelogram OPSQ. The resultant vector is represented by diagonal `\vec{R}` of the parallelogram. The triangular law and parallelogram law are equivalent. It should be noted that while finding the resultant of two vectors by the parallelogram law of vector addition, the two vectors `\vec{A}`and `\vec{B}` should either act towards a point or away from a point

(iii). Polygon law

The law states that if a number of vectors are represented in magnitude and direction by the side of an open polygon taken in the same order, the closing side of the polygon taken in reverse order will represent the resultant of these vectors in magnitude and direction.

`\vec{R}=\vec{P}+\vec{Q}+\vec{S}+\vec{T}`

Rectangular components of 3D-Vector

If three components of `\vec{A}` be Ax with x-axis, Ay with y-axis and Az with z-axis, then `\vec{A}` can be written as

`\vec{A}=\vec{A}_{x}\hat{i}+\vec{A}_{y}\hat{j}+\vec{A}_{z}\hat{k}`

In the form of unit vector,`\vec{A}` can be written as

`\vec{A}=\frac{\vec{A}_{x}\hat{i}+\vec{A}_{y}\hat{j}+\vec{A}_{z}\hat{k}}{|\vec{A}|}`

`\vec{A}=\frac{\vec{A}_{x}\hat{i}}{|\vec{A}|}+\frac{\vec{A}_{y}\hat{j}}{|\vec{A}|}+\frac{\vec{A}_{z}\hat{k}}{|\vec{A}|}`

If `\vec{A}` makes an angle α with x-axis, β with y-axis and γ with z-axis, then

`cos\alpha=\frac{A_{x}}{A},cos\beta=\frac{A_{y}}{A},cos\gamma=\frac{A_{y}}{A}`

where cosα, cosβ and cosγ are the direction cosines of vector A with positive x, y and z axes respectively.

`cos^{2}\alpha+cos^{2}\beta+cos^{2}\gamma=\frac{A_x^{2}+A_y^{2}+A_z^2}{A^2}`

`cos^{2}\alpha+cos^{2}\beta+cos^{2}\gamma=\frac{A^{2}}{A^{2}}`

`cos^{2}\alpha+cos^{2}\beta+cos^{2}\gamma=1`

Projectile Motion

When a particle is thrown obliquely near the surface of earth it moves along a curved path (known as parabolic path). Such a particle is called a projectile and its motion is called projectile motion. Projective motion is an example of plane motion. Ex : motion of a football, a cricket ball, a baseball etc.

(i). Equation of Trajectory

The above equation is called the equation of trajectory. As the equation represents a parabola. Thus, the trajectory (or the path) of a projectile is a parabola. Here, u, θ, x and y are four variables. If any three quantities, as mentioned, are known then the fourth quantity can be solved directly.

(ii). Time of Flight (T)

The time taken by a projectile to return its initial elevation after projection is known as time of flight. It is denoted by (T) and given by

`T=\frac{2u.sin\theta}{g}`

(iv). Maximum Height Attained

The maximum vertical height traveled by the projectile during its journey is called the maximum height attained by the projectile. It is denoted by `H_max` and given by

`H_{max}=\frac{u^2.sin^2\theta}{2g}`

(v). Horizontal Range

The maximum horizontal distance between the points of projection and the point of horizontal plane where the projectile hits is called horizontal range. It is denoted by R and give by

`R=\frac{u^2.sin2\theta}{g}`

Note : The range of projectile will be maximum if θ = 45

Relative Velocity

The velocity of a particle depends on the reference frame from where the particle is observed. A reference frame is a physical object to which we attach our coordinate system. If you observe the motion of a flying kite while standing on the ground, your reference frame is the ground and if you observe the motion of kite from inside a car moving on the ground, your reference frame is the car.

The velocity of the kite will be different for these two reference frames. Velocities observed from the ground are called velocity of object relative to the ground and the velocity of object A observed from the object B are called velocity of A relative to (or w.r.t.) B.

Uniform Circular Motion

When an object follows a circular path at a constant speed, the motion of the object is called uniform circular motion.

v = ωr

(i). Centripetal Acceleration

the acceleration of an object moving with speed v in a circle of radius R has a magnitude v2 /R and is always directed towards the centre. This is why this acceleration is called centripetal acceleration.

a = v2 / R = ω2r

(ii). Angular Position

At an instant the angle θ made by the position vector `\vec{r}` of the particle with the positive direction of x-axis is called the angular position of particle. The angular position θ keeps on changing with time.

(iii). Angular Velocity

The angular velocity of particle at any instant is defined as the rate of change of angular position θ. That is,

`\vec{ω}` = d`\vec{θ}` / dt

The angular velocity is measured in radian per second. In the above expression dθ is the infinitesimal angular displacement which is a vector quantity directed normal to plane of circular motion. This means that the angular velocity is a vector in the direction of dθ.

Angular Acceleration

The angular acceleration α at an instant is defined as the rate of change of angular velocity (ω) w.r.t. time. That is,

α = dω / dt

The direction of α is in the direction of ω if the angular speed increases with time and the α is opposite to ω if the angular speed decreases with time.

Summary

Scalar quantities are quantities with magnitudes only. Examples are distance, speed, mass and temperature.

Vector quantities are quantities with magnitude and direction both. Examples are displacement, velocity and acceleration. They obey special rules of vector algebra.

A vector A multiplied by a real number λ is also a vector, whose magnitude is λ times the magnitude of the vector A and whose direction is the same or opposite depending upon whether λ is positive or negative.

Two vectors A and B may be added graphically using head-to-tail method or parallelogram method.

Vector addition is commutative : A + B = B + A. It also obeys the associative law : (A + B) + C = A + (B + C).

Uniform circular motion: Motion in which an object goes along a circular path at a constant speed is called uniform circular motion.

Equal vectors: Two vectors having same direction and equal magnitude are called equal vectors. Equality of vectors is denoted as A॥ B.

Null vector: A vector having zero magnitude is called a null vector. It has no specific direction. It is denoted by 0.

Unit vector: A vector having unit magnitude and used to specify a particular direction is called unit vector. It has no unit. It is denoted by  etc.

Projectile: A projectile is any body which once thrown or projected into space with some initial velocity moves thereafter under the influence of gravity alone. For example, a football thrown in air, an arrow shot from its bow, a bullet fired from a rifle etc.

Time of flight: The total time for which a projectile remains in flight is called its time of flight.

Horizontal range: The horizontal distance traveled by a projectile during its flight is called its horizontal range.

Centripetal acceleration : The acceleration of an object moving in a uniform circular motion is called centripetal acceleration. It is mathematically given by a = v2/R. It is always directed towards the centre.

Angular Displacement (Δθ) : The angle swept out by the radius vector, when a particle moves along a circular path, is called its angular displacement.

Angular speed (ω) : The rate of change of angular displacement ω = Δθ / ΔT.

Time period : Time taken to complete one revolution by an object.

Frequency : Number of revolutions completed in unit time is called frequency.